- Paper: On the Theoretical Limitations of Embedding-Based Retrieval (arXiv:2508.21038v1, submitted August 28, 2025). This is a preprint that has not yet undergone peer review.

- Presenter: Hongsup Shin

- Attendees: Athula Pudhiyidath, Ivan Perez Avellaneda

This paper tackles a fundamental question that’s becoming increasingly relevant as embedding models are required to solve more complex retrieval tasks. The authors connect communication complexity theory to modern neural language model embeddings, and argue that the combinatorial explosion of possible top-k document sets will inevitably overwhelm fixed-dimensional embeddings. Given our interest in retrieval architectures and their fundamental capabilities, this paper offers an interesting theoretical lens, and tries to expand their idea with empirical experiments based on a synthetic dataset.

Paper summary

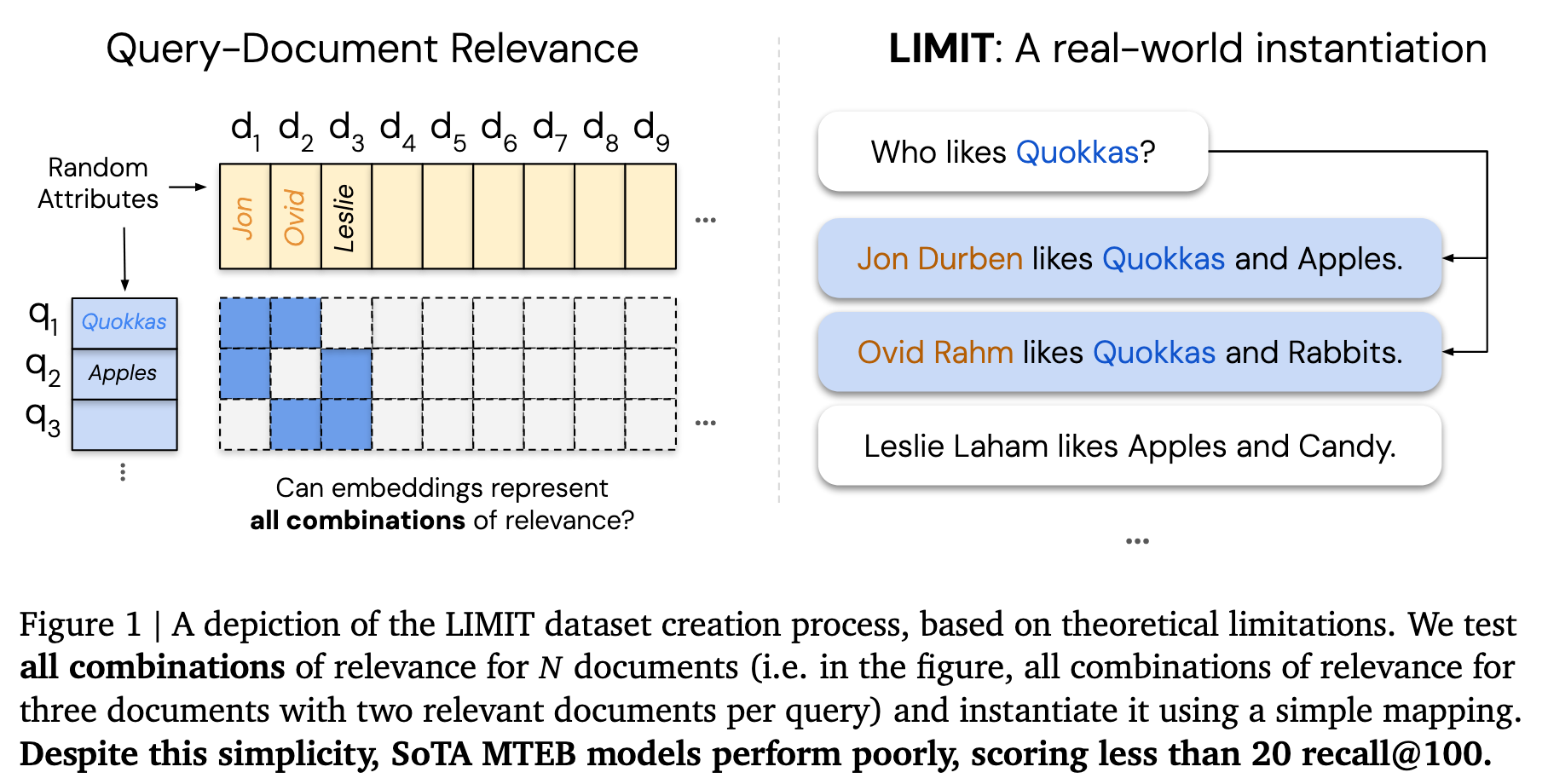

The core theoretical contribution connects the sign-rank of a query-relevance matrix (qrel, where rows represent queries and columns represent documents) to the minimum embedding dimension needed to represent it. Specifically, the authors prove that for a binary relevance matrix A, the row-wise order-preserving rank is bounded by \(\text{Rank}_{\pm}(2A - 1) - 1 \leq \text{Rank}_{\text{rop}}(A) \leq \text{Rank}_{\pm}(2A - 1)\), where \(\text{Rank}_{\pm}\) denotes the sign-rank and \(\text{Rank}_{\text{rop}}(A)\) represents the minimum embedding dimension needed to correctly order documents for all queries. This means that for any fixed dimension d, there exist combinations of top-k documents that cannot be represented regardless of the query.

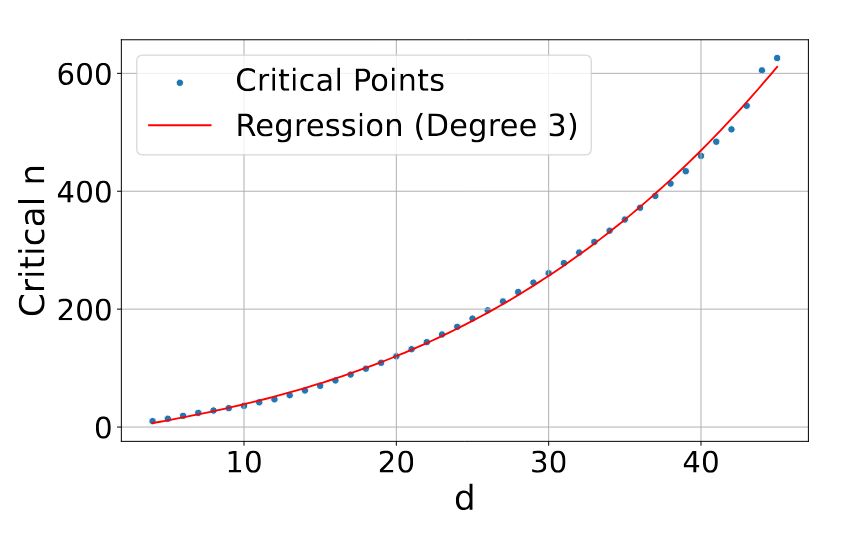

To validate this empirically, the authors conduct free embedding (simulated embeddings that are unconstrained by natural language) experiments where they directly optimize query (without backpropagation) and document vectors using gradient descent. They find that for k=2, there exists a critical point for each dimension d where the number of documents becomes too large to encode all combinations. Fitting these critical points across dimensions yields a smooth polynomial relationship that is monotonically increasing.

The experimental evaluation relies heavily on testing models at various embedding dimensions, which brings up an important technique: Matryoshka Representation Learning (MRL); think Russian dolls. MRL is a training technique that enables embeddings to maintain meaningful representations when truncated to smaller dimensions. It achieves this by using a loss function that combines losses computed at multiple embedding dimensions simultaneously. This trains the model so that the first d dimensions contain a complete (if lower-fidelity) representation, rather than requiring all N dimensions. This is crucial because naively truncating a standard embedding model’s 4096-dimensional output to, say, 512 dimensions would destroy the representation, as those first 512 dimensions were not optimized to be independently meaningful.

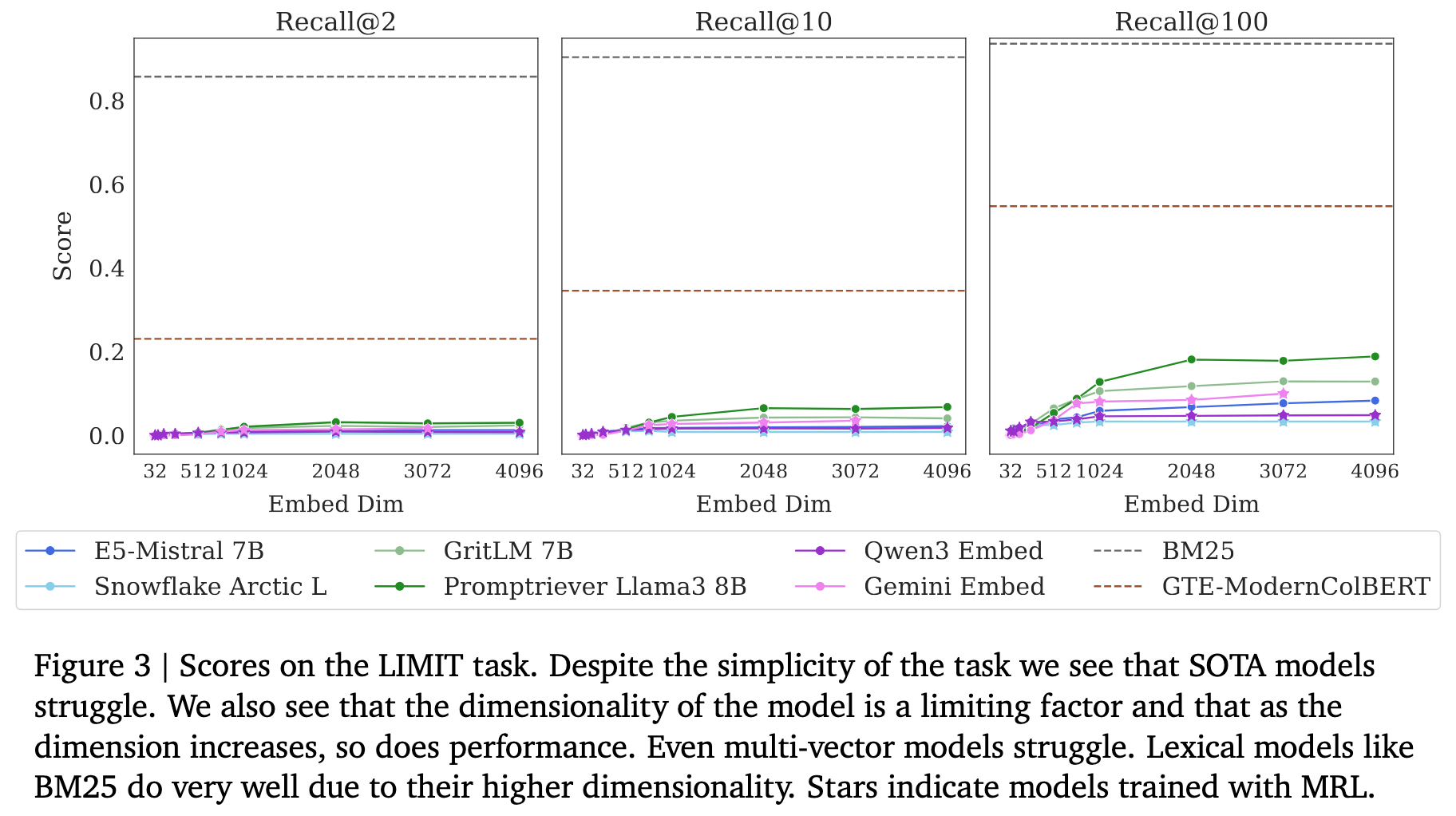

The paper tests both MRL-trained models (which can be fairly evaluated at smaller dimensions) and standard models (where truncation introduces severe artifacts), though not all models in comparison use MRL techniques, implying that potential severe loss in information may have occurred in smaller embedding spaces.

The authors then create LIMIT, a dataset designed to stress-test this limitation using natural language. Documents describe people and their preferences (e.g., “Jon likes Quokkas and Apples”), and queries ask “Who likes X?” Despite this simplicity, state-of-the-art embedding models achieve less than 20% recall@100, while BM25 scores above 90%.

Below is an example of a document in the LIMIT corpus:

{“_id”: “Olinda Posso”, “title”: ““,”text”: “Olinda Posso likes Bagels, Hot Chocolate, Pumpkin Seeds, The Industrial Revolution, Cola Soda, Quinoa, Alfajores, Rats, Eggplants, The Gilded Age, Pavements Ants, Cribbage, Florists, Butchers, Eggnog, Armadillos, Scuba Diving, Bammy, the Texas Rangers, Grey Parrots, Urban Exploration, Wallets, Rainbows, Juggling, Green Peppercorns, Dryers, Pulled Pork, Holland Lops, Blueberries, The Sound of Wind in the Trees, Apple Juice, Markhors, Philosophy, Orchids, Risk, Alligators, Peonies, Birch Trees, Stand-up Comedy, Cod, Paneer, Environmental Engineering, Caramel Candies, Lotteries and Levels.”}

The paper concludes by briefly examining alternatives to single-vector embeddings that might avoid these theoretical limitations. Cross-encoders (e.g., Gemini-2.5-Pro, which uses a long context reranker) successfully solve the LIMIT task with 100% accuracy but remain too computationally expensive for first-stage retrieval at scale (note: the details of how they conducted this experiment are quite vague). Multi-vector models like ColBERT show improvement over single-vector approaches (though still fall short of solving LIMIT), while sparse models like BM25 succeed due to their effectively much higher dimensionality. However, the authors note it’s unclear how sparse approaches would handle instruction-following or reasoning-based tasks without lexical overlap.

Strengths

The theoretical motivation is quite interesting. Connecting sign-rank to retrieval capacity provides a formal framework for understanding embedding limitations, and the proof itself is clean, well-constructed, and relatively easy to follow. The observation that as retrieval tasks require representing more top-k combinations (especially through instruction-based queries connecting previously unrelated documents), models will hit fundamental limits is genuinely important for the field.

The authors’ decision to test models across different embedding dimensions using MRL is commendable. While the execution has issues (inconsistent treatment of MRL and non-MRL models, unclear figure legends), the underlying motivation to examine information loss in truncated embeddings is sound and addresses an important question.

Finally, we liked that the authors tried to bridge theory and practice by creating a concrete dataset. Many theoretical papers stop at proofs and toy examples, but the LIMIT dataset represents a genuine effort to operationalize the theoretical limitations. The dataset takes the abstract notion of “all top-k combinations” and maps it to natural language. The progression from free embedding experiments (pure mathematical optimization) to synthetic but linguistic data (LIMIT) to comparisons with models trained on existing benchmarks (MTEB, BEIR) shows methodological rigor in trying to validate the theory at multiple levels of abstraction. Even if the execution has flaws, the attempt to move beyond pure theory into testable predictions is highly valuable.

Weaknesses

However, we found the gap between theoretical insight and experimental validation concerning. Several fundamental issues may undermine the paper’s claims:

Experimental methodology issues

Free embedding experiments are questionable as “best case”

The authors frame free embedding optimization as the ‘best case’ scenario, arguing that if direct vector optimization cannot solve it, real models won’t either. But this “unconstrained = best” logic reasoning conflates representational capacity with optimization tractability. Inductive biases in real models (e.g., semantic structure learned from language) don’t just constrain what can be represented, but they actively guide optimization by shaping the loss landscape. Free embeddings optimizing in unconstrained high-dimensional space may actually face harder optimization challenges than semantically grounded models, potentially getting trapped in poor local minima precisely because they lack guiding structure. Whether free embedding failure truly upper-bounds neural retriever performance, or simply reflects different optimization dynamics, remains unclear.

Flaws in experimental design regarding varying embedding sizes

The dimension ablation experiments are particularly problematic. When evaluating models at different dimensions d < N (where N is the model’s native dimension), they simply truncate to the first d dimensions. This causes massive information loss because these dimensions were not trained to be independently meaningful at arbitrary truncation points. Even for models trained with MRL, which does enable meaningful truncation, the paper is inconsistent about which models used MRL versus which were naively truncated.

The domain shift experiment suffers from the same truncation issue, making it hard to disentangle whether poor performance stems from domain mismatch or from damaged representations. Moreover, this experiment relies solely on fine-tuning without providing sufficient detail on whether the limited data samples were adequate to meaningfully change embedding behavior. With smaller dimensions especially, full training (rather than fine-tuning) might have been more appropriate, though we acknowledge this would be computationally expensive. Fine-tuning with truncated naive embeddings (which suffer from severe information loss) doesn’t convincingly demonstrate the authors’ point about theoretical limitations—it may simply reveal the inadequacy of the fine-tuning approach itself.

Missing theoretical depth in key places

The polynomial fit to the critical-n points (Figure 2) is impressively smooth, suggesting deeper theoretical structure that remains unexplored. Why specifically a degree-3 polynomial? Is there a theoretical derivation for this functional form, or is it purely empirical? Similarly, the connection to order-k Voronoi diagrams is mentioned but dismissed as “computationally infeasible” and “notoriously difficult to bound tightly” without much detail.

Despite deriving a polynomial relationship between dimension and critical document count, the paper disappointingly provides no practical guidance. A natural question remains unanswered: given N documents with k-attribute queries, what minimum embedding dimension is needed? The fitted curve could inform such estimates, but the authors do not discuss whether their framework enables practical dimensionality recommendations or what additional work would be required to derive them.

The qrel pattern experiments (Figure 6) show that “dense” patterns are much harder than random, cycle, or disjoint patterns, but no theoretical framework connects the patterns to sign-rank. These experiments are also where exploring different values of k could have been particularly informative.

Dataset design problems

LIMIT doesn’t test what it claims to test

The LIMIT dataset has a fundamental mismatch. While queries are simple (‘Who likes Quokkas?’), the documents are highly unnatural. Each document lists approximately 50 randomly assigned attributes, a structure difficult to be found in natural language. This creates what is essentially a memorization stress test rather than a semantic understanding task. Documents like ‘Olinda Posso likes Bagels, Hot Chocolate, Pumpkin Seeds, The Industrial Revolution, Cola Soda, Quinoa…’ (continuing for ca. 50 items) bear very little resemblance to natural text. The fact that BM25 achieves over 90% while neural models struggle below 20% is revealing: this task rewards exact term matching (lexical memorization) rather than semantic understanding.

Limited exploration of k undermines the combinatorial complexity claim

The paper’s central thesis is that combinatorial complexity fundamentally limits embeddings, yet the empirical validation examines only k=2. If combinatorial explosion is truly the core issue, the natural experiment is to vary k systematically (k=2, 3, 4, 5…) and demonstrate where and how performance degrades. Without this, their argument on combinatorics becomes weak.

Moreover, k=2 represents a fundamentally shallow per-instance retrieval task: each query asks only whether two specific attributes co-occur in a document. This is qualitatively different from queries requiring inference, reasoning, or understanding complex semantic relationships. The difficulty comes not from the cognitive complexity of individual queries, but from the sheer volume of attribute combinations to memorize numerous pairs. This is combinatorial overload of a simple operation rather than genuine semantic complexity. The paper’s claim about combinatorial limitations would be more compelling if tested on queries that actually require complex reasoning for each instance, not just checking membership in a memorized list.

Superficial analysis

The MTEB correlation analysis is superficial

The paper compares SOTA models’ poor LIMIT performance with BEIR performance (Figure 7, Section 5.5), and suggests that “smaller models (like Arctic Embed) do worse on both, likely due to embedding dimension and pre-trained model knowledge.” Yet large models like E5-Mistral (4096-d) also score poorly on LIMIT. The correlation analysis doesn’t support strong conclusions either way, and the discussion of dimension dependence is hand-wavy given that high-dimensional models also struggle.

The “alternatives” section adds little

Given these limitations in the empirical validation, the paper’s brief discussion of alternatives to single-vector embeddings feels incomplete. The discussion of cross-encoders, multi-vector models, and sparse retrievers is disappointingly shallow. These are well-known alternatives, and the paper provides no new insights about how they circumvent the theoretical limitations or what trade-offs they entail at scale. The observation that ColBERT performs better offers little explanation of why or what this tells us about the limitations.

Absolutist framing obscures nuance

The paper tests one narrow scenario (k=2, synthetic memorization task), finds poor performance, and then makes sweeping claims like “embedding models cannot represent all combinations” without adequate explanation or qualification. The framing presents binary success/failure when the real questions are graded and contextual: which combinations matter in practice? How much worse is performance, and in what ways? Would these limitations manifest in real-world retrieval scenarios with natural language?

Moreover, the embedding models achieved about 20% recall, not zero, yet there is no analysis of which queries or combinations succeeded versus failed. Understanding this pattern, especially across different embedding dimensions, could reveal whether failures are random or systematic and whether certain types of combinations are more representable than others. This would provide far more insight than aggregate failure rates alone.

Final thoughts

This paper doesn’t fully deliver on its promise. The theoretical contribution is solid and potentially important, but the empirical validation is flawed and does not support the strong claims being made. The sign-rank framework provides a useful lens for thinking about embedding capacity, and the paper does demonstrate something real: state-of-the-art neural embedding models struggle to exhaustively memorize even small combinatorial spaces (k=2 combinations). This empirical finding is noteworthy, even if the authors don’t analyze which combinations succeed versus fail or whether certain patterns are systematically more difficult.

However, without cleaner experiments that separate genuine theoretical limits from artifacts of poor experimental design, we can’t conclude whether state-of-the-art models are hitting fundamental boundaries or simply failing at an artificial memorization task with broken evaluation methodology. The theoretical limitations are real—the question is whether they matter for realistic semantic retrieval tasks, where queries require understanding meaning and context rather than exhaustively memorizing unnatural attribute lists. The paper raises important questions about the future of instruction-based retrieval and alternatives to single-vector embeddings, but doesn’t yet provide convincing evidence that these theoretical limits will constrain models on practical retrieval tasks.

If you found this post useful, you can cite it as:

@article{

austinmljc-2025-embedding-retrieval-limitations,

author = {Hongsup Shin},

title = {On the Theoretical Limitations of Embedding-Based Retrieval},

year = {2025},

month = {09},

day = {25},

howpublished = {\url{https://austinmljournalclub.github.io}},

journal = {Austin ML Journal Club},

url = {https://austinmljournalclub.github.io/posts/20250925/},

}