Why this paper?

Data leakage is a problem that we have all encountered as data scientists and scientific researchers. We just never knew how big! I was drawn to this paper because it attempts to quantify the impact of data leakage. It presents the unique view of considering the impact on ML-based science and shows how widespread and problematic data leakage is and leads to exaggerated claims of predictive performance. However, the frequency of data leakage and the impact of making these types of mistakes could be just as high or higher for ML-based industry applications. As a mixed group of ex ML-based science practitioners and current ML-based industry practitioners, I thought it would be insightful to discuss the eight types of data leakage identified, the proposed mitigation strategy of filling out model info sheets for ML-based science, and if the presented solution is also reasonable for a variety of ML-based industry applications.

Defining the leakage and the reproducibility crisis in ML-based science

This first thing this paper does is narrow the scope of relevant literature to only papers that are used for ML-based science. The authors define ML-based science as only papers “making a scientific claim using the performance of the ML model as evidence.” Furthermore, research findings are termed reproducible “if the code used to obtain the findings are available and the data is correctly analyzed.” Lastly, data leakage is a “spurious relationship between the independent variables and the target variables that arises as an artifaction of data collection, sampling, or pre-processing strategy.” Based on these three definitions, 20 papers with data leakage in 17 fields were found to impact a total of 329 ML-based research papers. These authors make three explicit contributions: 1) present a unified taxonomy of eight types of data leakage that lead to reproducibility issues, 2) propose the use of model info sheets to identify and prevent leakage, 3) quantify the impact of data leakage on model performance of civil war predictions.

The first thing we noticed when looking at Table 1 was that several of the fields are areas with potential high-stakes such as medicine, clinical epidemiology, neuropsychiatry, medicine, and radiology. Engineering applications were excluded from this analysis but several fields sounded very close to this industry such as software engineering and computer security. We didn’t feel that ML-based science should be differentiated from industry-based ML applications. If anything, we felt that data leakage in industry applications may be harder to detect because they lack a formal peer review process and could have a bigger impact because these models are deployed in the real world.

Data leakage taxonomy

- L1.1 No test set: This was shocking to us. How does the peer review process allow these papers to be published? Hopefully, in the future reviewers will be more demanding of ML practitioners. This is also the most common type of data leakage identified in Table 1.

- L1.2 Pre-processing on training and test set: We felt that this was a loaded category. There are many different ways for this type of data leakage to come about. For example, during imputation, under/oversampling, and encoding. For clarity, we thought this category could have been subdivided.

- L1.3 Feature selection on training and test set: This is the second most common type of data leakage found in Table 1.

- L1.4 Duplicates in dataset: This seems more like an error than a type of data leakage.

- L2 Model features that aren’t legitimate: We spent the most time discussing this category. We found it hard to think about proxy variables because they require a lot of domain knowledge. Instead, we like the definition of a feature the model would not have access to when making new predictions.

- L3.1 Temporal leakage: This is when future data is included in model training.

- L3.2 Non-independence between training and test samples: This can be caused by resampling the same patient or geographic location. This type of leakage can also be due to the interpretation of the results. This occurs when there is a mismatch between the test distribution and the scientific claim.

- L3.3 Sampling bias in test distribution: This is choosing a non-representative subset for analysis.

In general, categories L1.1-4 are clear cut and should be identifiable and avoidable. L2 is difficult because it depends on domain knowledge. Due to the nature of collaboration the researcher with this expert domain knowledge may not be the individual performing the ML analysis. Similarly, L3.1-3.3 are also difficult to detect and avoid if the researcher is using previously collected data and not designing an experiment and collecting data from scratch. In industry, data is often given to ML practitioners and there is no option to immediately collect more data or change the collection methodology. If this is the case, data leakage could be undetectable in many industry applications as ML practitioners are working with the best data at hand. In addition, there are limited strategies for identifying and mitigating these three types of data leakage.

Model info sheets to mitigate data leakage

We appreciated that the authors suggested a mitigation strategy. We found the questions in the model info sheets to be a useful sanity check for any ML practitioner. However, the level of detail requested from the info sheets would likely only be filled out if peer reviewed journals required it. Even if journals require model info sheets as part of the peer review process, we agree with the authors that there are still limitations. Most notably, the claims in the model info sheets can’t be verified without the code, computing environment, and data. There are some scientific research fields where authors might be unwilling or unable to disclose all information due to privacy concerns. In addition, there is nothing to prevent authors from lying or not having the ML expertise to fill out the model info sheet correctly. Since ML has become more accessible to non-ML experts, subtle cases might not easily be noticed by the author or reviewer.

In industry, data privacy is also a concern but ML practitioners within a company could use these model info sheets to identify data leakage in industry based applications. However, there is no way to enforce this across companies or for a user of an industry based ML application to determine if the results are sound. Industry based ML is growing and there are often many groups within a company experimenting with ML. From what we have seen, there are no established within-company standards let alone between-company standards that would require the use of model info sheets to prevent data leakage.

Civil war predictions

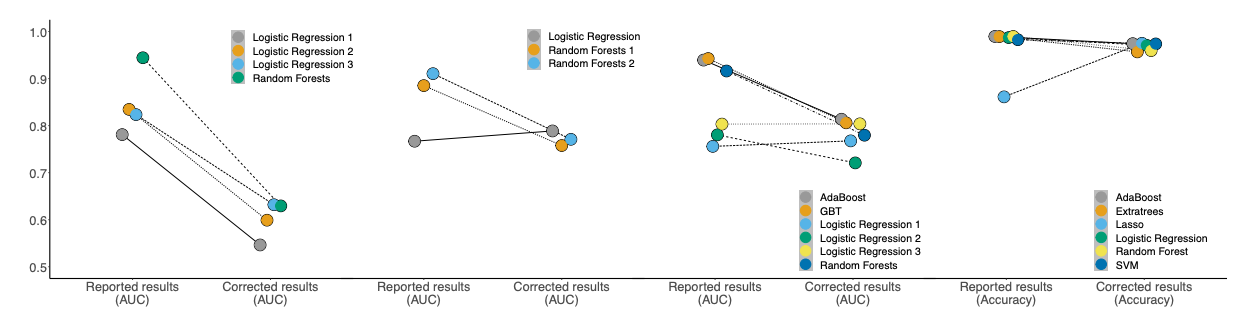

To understand the impact of data leakage the authors present a case study on civil war predictions. They identified 12 papers on the topic that provided the code and data. Of the 12 papers identified, four claimed superior performance of complex ML models compared to logistic regression. When all types of data leakage were identified and fixed, the complex models did not outperform logistic regression (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows how the performance metric is reduced after data leakage is corrected. In particular, we noticed that model performance of the simple logistic regression model was not impacted as much by data leakage compared to the complex (tree-based) ML methods. We wish the authors had speculated on why.

Final thoughts

Data leakage is a big issue that is not highlighted enough. The authors focused their efforts on identifying data leakage in ML-based science. While we appreciate them proposing a solution to identify and prevent data leakage, we think filling out model info sheets is a big ask and unlikely to be a common practice unless required by the peer review process. In addition, there are efficacy issues with model info sheets and it will be impossible to substantiate each claim. Industry ML applications are likely facing similar challenges with data leakage as ML-based science but these effects will be even more challenging to detect and quantify.

If you found this post useful, you can cite it as:

@article{

austinmljc-2023-data-leakage,

author = {Kate Behrman},

title = {Leakage and the Reproducibility Crisis in ML-based Science},

year = {2023},

month = {01},

day = {26},

howpublished = {rl{https://austinmljournalclub.github.io}},

journal = {Austin ML Journal Club},

url = {https://austinmljournalclub.github.io/posts/20230126/},

}